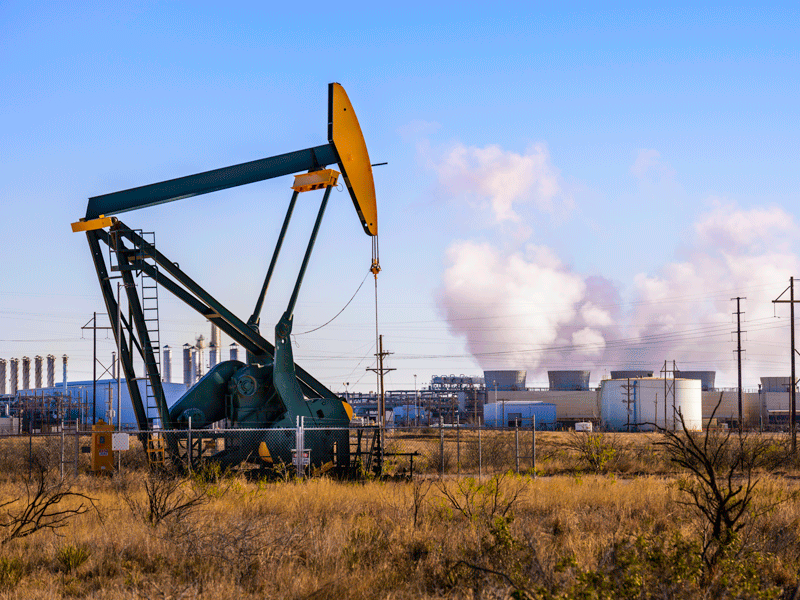

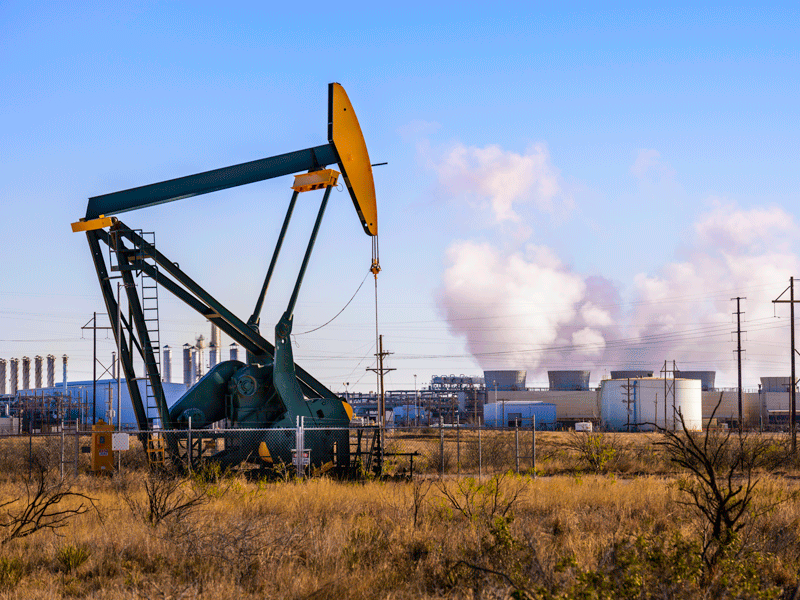

Poor infrastructure is threatening to derail the US shale boom

US shale output

continues to soar in the Permian basin, but worries about poor infrastructure

hampering production won’t go away

The huge amounts of oil and gas that are being

extracted from the Permian Basin are causing frustrating bottle necks for

producers in the region

This July, the US crude

oil industry celebrated a groundbreaking moment when its output

averaged an estimated 11 million barrels per day (BPD) for the first time ever

(see Fig 1). This makes the US the world’s second-largest producer,

behind only Russia. The surge is largely down to the boom in shale oil and gas

production in the Permian Basin across the west of Texas and south-east New

Mexico. Drilling in the region began to ramp up a decade ago, and it is only projected

to continue growing. But there is one hurdle standing in the way: a lack of

critical infrastructure.

It is not just oil

pipelines that are unable to keep up with demand – the associated natural gas

production has also overwhelmed the system

In recent months,

producers have experienced pipeline bottlenecks due to the vast amounts of oil

and gas being pumped out of the Permian Basin, where output has reached around

3.4 million BPD. With the current pipeline capacity sitting at approximately

3.56 million BPD, analysts expect the constraints to begin limiting growth in

the region next year.

Growing pains

before the rapid development of America’s shale industry caused a new surge in crude output; US oil production peaked at about 9.6 million BPD in 1970. After that, it decreased steadily, falling as low as five million BPD in 2008. Around this time, however, producers revolutionized the industry by using hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, and horizontal drilling to extract oil and gas trapped in reservoir rocks. Production soared at the fastest pace in the country’s history, upending the global oil and gas industry.

before the rapid development of America’s shale industry caused a new surge in crude output; US oil production peaked at about 9.6 million BPD in 1970. After that, it decreased steadily, falling as low as five million BPD in 2008. Around this time, however, producers revolutionized the industry by using hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, and horizontal drilling to extract oil and gas trapped in reservoir rocks. Production soared at the fastest pace in the country’s history, upending the global oil and gas industry.

The Permian Basin is at

the center of the US shale boom. It is one of the world’s thickest deposits of

rocks from the Permian geologic period, and along with the legendary Ghawar

Field in Saudi Arabia, the Permian is one of the worlds most prolific. Since

2012, production there has grown by about two million BPD, which is more than

any other field.

It is estimated that

another 75 billion barrels of recoverable oil lie within the Permian. Brian

Collins, a senior researcher at S&P Global Market Intelligence, told World

Finance that this basin will be the “mainstay for US production for

the foreseeable future”.

Its success, however, is

beginning to highlight cracks in the area’s infrastructure. By the end of 2018,

BP Capital Fund Advisors expects production to exceed available pipeline space

by 300,000 to 400,000 BPD. By 2019, that gap will rise to 750,000 BPD, causing

a “significant” amount of oil to be stranded in the basin.

And it is not just oil

pipelines that are unable to keep up with demand – the associated natural gas

production has also overwhelmed the system, and the accompanying water that is

produced is becoming a problem too. For every barrel of oil produced, between

three and five barrels of contaminated water must also be piped away.

Additionally, more pipelines will soon be needed to handle natural gas liquids,

which are components of natural gas.

“So we’ve got basically

four different infrastructure systems that are extremely challenged right now.

This basin is not going to stop growing, either. It’s going to keep growing as

these companies expand across it,” Collins said.

Shifting away

as news came to light in May that pipeline bottlenecks were constraining crude shipments, the share prices of companies based in the region started to slide. At the beginning of June, Bloomberg reported that eight of the basin’s pure-play drillers had lost $15.6bn in combined market value in just two weeks – or around $1bn a day.

as news came to light in May that pipeline bottlenecks were constraining crude shipments, the share prices of companies based in the region started to slide. At the beginning of June, Bloomberg reported that eight of the basin’s pure-play drillers had lost $15.6bn in combined market value in just two weeks – or around $1bn a day.

2 million

The growth in BPD

production in the Permian Basin since 2012

3.4 million

The BPD production

capacity in the Permian Basin

3.56 million

The BPD capacity of

pipelines in the Permian Basin

What’s more, oil

behemoth BP recently revealed its oil trading unit had swung to a quarterly

loss due to the Permian bottlenecks, which have led producers in the region to

sell their crude at a hefty discount relative to benchmark West Texas

Intermediate prices. While the spread was as little as 40 cents at the

beginning of the year, it reached between $15 and $20 a barrel in August. This

discount is expected to persist for at least another year.

Not only are producers

grappling with discounts on their oil, but in response to the squeeze companies

have also been forced to go down the expensive route of storing their crude or

driving it hundreds of miles on trucks to pipelines in other parts of the

state.

Because of this,

ConocoPhillips – one of the top oil producers in the US – revealed in June that

it would temporarily redeploy resources out of the Permian Basin. “We have

other opportunities to go spend our capital,” CEO Ryan Lance told the Financial

Times. “And I am not sure it makes sense to drill into that headwind.” A

number of other companies both big and small are beginning to “shift their

emphasis to other basins”, Collins said.

But while oil and gas

firms with deep pockets can wait around for returns on their investments, the

midstream companies that build the desperately needed infrastructure cannot

make investments into pipelines without knowing if they will receive a steady

volume of oil or gas.

“An issue right now is a

lot of the natural gas pipelines that are needed are having a hard time getting

off the ground because producers are not necessarily used to having to pay

somebody to build them a pipeline to get rid of their gas,” Collins said. Even

one of the largest pipeline builders in the US, Kinder Morgan, is conservative

about the prospect of building new pipelines.

The big fix

According to BP Capital, “meaningful relief” is set to come to the Permian in the second half of 2019 with the set-up of key long-haul pipelines, such as EPIC, Gray Oak and Cactus II. The International Energy Agency (IEA) said TexStar Midstream Logistics’ EPIC pipeline – one of the biggest and most advanced projects in development – “holds the key to solving pipeline bottlenecks in 2019”.

According to BP Capital, “meaningful relief” is set to come to the Permian in the second half of 2019 with the set-up of key long-haul pipelines, such as EPIC, Gray Oak and Cactus II. The International Energy Agency (IEA) said TexStar Midstream Logistics’ EPIC pipeline – one of the biggest and most advanced projects in development – “holds the key to solving pipeline bottlenecks in 2019”.

The pipeline was

originally set to carry 440,000 BPD, but it could be upgraded to transport

675,000 BPD due to high demand. Once these pipelines are in place, crude oil

produced in the region is expected to stop selling at a discount compared with

benchmark prices.

In BP Capital’s view,

the sell-off in the region’s exploration and production firms was “overly

severe and particularly short sighted”. The firm stressed in an online article

that the bottlenecks are a “relatively short-term issue that does not diminish

the long-term attractiveness and potential of the Permian Basin”.

While it is true the

basin remains attractive for many producers, the IEA expects output to grow at

a slower rate in 2019 as pipeline capacity remains tight. The Paris-based

agency predicted output would rise by 1.3 million BPD this year and just

900,000 BPD in 2019. According to the IEA: “Pressure on midstream

infrastructure and pipeline capacity out of the Permian and Eagle Ford basins

in Texas is unlikely to be resolved before the second half of 2019. Labor

shortages, road congestion and water disposal constraints could also contribute

to curbs in expansion in the short term.”

There are additional

concerns that the pipeline projects could face delays. Analysts at Morgan

Stanley expect slowdowns of three to six months for some projects due to the

complexity of the proposed lines. This could lead to the production of just

360,000 BPD in the Permian Basin in 2019, Morgan Stanley said. Some midstream

companies also face higher-than-expected material costs because of President

Donald Trump’s 25 percent tariff on steel imports. For Plains All American

Pipeline, which is building the 585,000-BPD Cactus II pipeline, the tariff has

increased the cost of its $1.1bn pipeline by about $40m.

However, it is unlikely

the basin’s problems will end in 2019. Production is expected to continue

ramping up in the region in the decades to come, and the planning process for

building pipelines appears to be flawed. Collins said a new type of financing

would be needed to allow producers to better cooperate with midstream players:

“If oil and gas companies actually formally commit and sign on to be a shipper

on a pipeline, that’s how these pipelines will get built.” Yet, Collins

admitted, most producers are reluctant to own their own pipeline.

Therefore, the ‘Wild

West’ environment is expected to continue. Collins said: “It seems like it’s

just going to be this odd situation where we’re going to get these pipelines

all built [and,] say two years from now, we have brought the pipeline space up

to where it can handle all of the natural gas and the liquid output. But then I

think that producers are going to continue to race along, and maybe this is

going to be a backwards-and-forwards kind of situation for many years.”

Although the new pipeline

projects face some potential hiccups, the current bottlenecks in the Permian

Basin are indeed a short-term problem. But the industry should take it as a

warning that until a more cooperative process is formed between producers and

pipeline builders, this could be the first glimpse of an issue that could plague

the future of one of the world’s top shale basins.

Comments

Post a Comment